Understanding Options: A Practical Guide for New Traders

When I first encountered options contracts, I made the same mistake many beginners make: I thought they were just a way to bet on whether stocks would go up or down. It took several losing trades and countless hours of study to understand that options are actually sophisticated financial instruments designed for specific purposes, each with distinct risk-reward profiles.

This guide shares what I've learned about how options actually work in practice, not just in theory. We'll explore real scenarios, discuss what can go wrong, and examine why most casual traders lose money with options while some institutional investors and disciplined traders use them effectively.

What Options Actually Represent

An option is a contract that gives you the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a stock at a specific price before a certain date. Think of it like a reservation system.

Imagine you're interested in buying a house currently listed at $400,000, but you won't have financing approved for two months. You could offer the seller $5,000 for the exclusive right to buy that house at $400,000 anytime in the next 60 days. If housing prices surge and the house becomes worth $450,000, you can still buy it for $400,000. If prices drop to $350,000, you simply walk away and lose your $5,000 reservation fee.

That's essentially how a call option works. A put option is the opposite scenario, giving you the right to sell at a predetermined price.

The Two Types of Contracts

Call options give you the right to purchase shares at a fixed price (the strike price). Traders buy calls when they believe a stock will rise significantly before the option expires.

Put options give you the right to sell shares at a fixed price. These are purchased when expecting a stock to decline, or as insurance against existing stock holdings.

Each options contract typically covers 100 shares of the underlying stock. This is crucial to understand because when you see an option quoted at $2.50, you're actually paying $250 for that contract ($2.50 × 100 shares).

Why Options Exist (And It's Not What You Think)

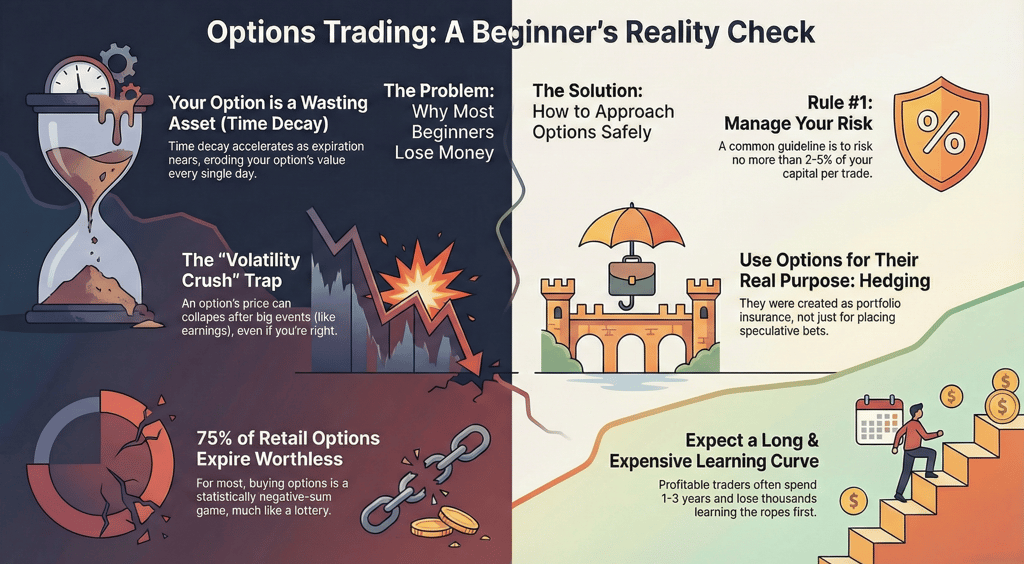

Here's something that surprised me: options weren't primarily designed for speculation. They were created for risk management.

Large institutional investors holding millions of dollars in stocks use options to protect against downside risk, similar to buying insurance for a house. Corporations use them to hedge against currency fluctuations or commodity price changes. Market makers use them to balance their portfolios and reduce exposure.

Speculation is actually a secondary use case, though it's become the primary reason retail traders get involved. This mismatch between design intent and actual usage is one reason why many individual traders struggle.

How Option Pricing Really Works

Option prices aren't arbitrary. They're determined by several factors, and understanding these is critical to avoiding expensive mistakes.

Intrinsic value is the amount an option is already "in the money." If you own a call option with a $50 strike price and the stock is trading at $55, that option has $5 of intrinsic value. You could exercise it immediately and make $5 per share (minus the premium you paid).

Time value represents the possibility that the option could become more profitable before expiration. An option expiring in three months has more time value than one expiring next week, simply because there's more time for the stock to make a favorable move.

Implied volatility might be the most important factor beginners overlook. It represents the market's expectation of how much the stock will move. When volatility is high, options become expensive because there's a greater chance of significant price swings. When volatility is low, options are cheaper.

Here's a real scenario that illustrates this: Before a company's earnings announcement, implied volatility typically spikes. An option that was trading at $3.00 might jump to $4.50 simply due to increased volatility, even if the stock price hasn't changed. After earnings are announced, volatility collapses. That same option might drop to $2.00 the next day, even if the stock moved in your favor. This phenomenon, called "volatility crush," has devastated countless traders who didn't understand what they were buying.

The Mathematics of Time Decay

Every option is a wasting asset. From the moment you purchase it, time decay (theta) is working against you.

The decay isn't linear. An option doesn't lose 1/30th of its value each day during its final month. Instead, time decay accelerates as expiration approaches. An option might lose 10% of its time value in its first week, but 50% in its final week.

Consider this example: You buy a call option for $5.00 with 30 days until expiration. The stock doesn't move at all. After one week, your option might be worth $4.50. After two weeks, $4.00. After three weeks, $3.00. In the final week, it could drop to $1.50, then $0.50, then expire worthless. You've lost 100% of your investment without the stock moving against you at all.

This is why buying options requires not just being right about direction, but also about timing. You can correctly predict a stock will rise, but if it doesn't happen before your option expires, you still lose.

Common Strategies and Their Hidden Costs

The Covered Call: Income or Missed Opportunity?

Selling covered calls means you own 100 shares of a stock and sell someone else the right to buy those shares at a higher price. You collect the premium immediately.

Let's say you own 100 shares of a technology stock trading at $80 per share. You sell a call option with a $90 strike price expiring in one month, collecting a $200 premium.

Three outcomes are possible:

If the stock stays below $90, the option expires worthless. You keep your shares and the $200. This scenario feels like free money, which is why the strategy is popular.

If the stock rises to $85, you keep your shares and the $200. You're happy, but you've capped your upside. Had you not sold the call, you'd have made $500 on your shares plus could still benefit from further gains.

If the stock surges to $105, your shares get called away at $90. You make $1,000 on the shares (bought at $80, sold at $90) plus the $200 premium, totaling $1,200. But the stock is now worth $10,500. You've given away $1,300 of gains. Meanwhile, the person who bought your call option made $1,300 from a $200 investment.

The covered call strategy works well in sideways or slowly appreciating markets. It's disastrous during strong rallies. Many investors learned this the hard way during the 2020-2021 market surge, watching stocks they'd sold calls on double or triple while they were locked into modest gains.

The Protective Put: Insurance Isn't Free

Buying put options to protect existing stock holdings is like buying insurance. It works, but the cost adds up.

Suppose you own 100 shares of a stock at $100 and you're worried about a potential decline. You buy a put option with a $95 strike price for $300, expiring in three months.

If the stock crashes to $70, your put option becomes worth approximately $2,500 (the $95 strike minus the $70 stock price, times 100 shares). Your stock loss is $3,000, but the put gain is $2,500, and you paid $300 for the put. Your net loss is $800 instead of $3,000. The insurance worked.

But if the stock stays at $100 or rises, your put expires worthless. You've spent $300 for protection you didn't need. Do this quarterly, and you're spending $1,200 per year insuring $10,000 worth of stock—a 12% annual cost that significantly erodes returns.

Professional portfolio managers use this strategy selectively, typically when they have specific concerns about market conditions but don't want to sell positions for tax or strategic reasons. Retail investors often overuse it, turning it into an expensive habit that guarantees underperformance during bull markets.

The Straddle: Betting on Movement

A straddle involves buying both a call and a put at the same strike price. You profit if the stock makes a large move in either direction.

This sounds like a can't-lose strategy until you understand the pricing. The market knows when big moves are expected. Before earnings announcements, product launches, or FDA decisions, implied volatility spikes, making both calls and puts expensive.

Here's a real scenario: A pharmaceutical company is awaiting FDA approval for a major drug. The stock trades at $50. You buy a $50 call for $4.00 and a $50 put for $4.00, spending $800 total.

The FDA approves the drug, and the stock jumps to $60. Your call is worth approximately $10.00 ($1,000), and your put is worthless. You invested $800 and your position is worth $1,000—a $200 profit, or 25% return. Not bad.

But what if the stock only rises to $55? Your call is worth about $5.00 ($500), your put is worthless, and you've lost $300 on an $800 investment despite correctly anticipating positive news.

The stock needs to move beyond what the market already expects (which is priced into the options) for you to profit. This is why buying straddles before earnings is often a losing proposition. The market has already priced in the expected move, and you need an unexpected surge to profit.

What the Statistics Actually Show

Research from the Chicago Board Options Exchange indicates that approximately 75% of all options held by retail traders expire worthless. This doesn't mean 75% of traders lose money (some traders sell options), but it highlights that buying options is a negative expected value game for most participants.

Why do traders keep doing it? The same reason lottery tickets remain popular. The winners are memorable and the payoffs can be spectacular. A $500 options position that turns into $5,000 creates a powerful psychological impression. The twenty $500 losses that preceded it are easier to forget or rationalize.

Successful options traders typically do one of two things: they sell options to collect premium from overeager buyers, or they use options as precise, calculated tools within a broader investment strategy, not as standalone bets.

Risk Management: What Actually Matters

The single most important rule in trading options is this: never invest money you can't afford to lose completely.

Unlike stocks, which can recover from declines, an option that expires worthless is gone forever. There's no "holding until it comes back" with options.

Position sizing is critical. A common guideline suggests risking no more than 2-5% of your trading capital on any single options trade. If you have $10,000 to trade, that means individual positions of $200-$500. This ensures that even a series of losses won't devastate your account.

Many beginners do the opposite. They risk 20-30% of their capital on a single "high-conviction" trade, often right before a catalyst event like earnings. When it goes wrong—and it will, repeatedly—they lose a significant portion of their capital in one trade.

Understanding implied volatility before entering trades is also essential. Buying options when implied volatility is at multi-year highs means you're paying top dollar for contracts that will likely decline in value even if the stock moves in your favor, due to volatility crush.

The Learning Curve Is Real and Expensive

Most traders who eventually become consistently profitable estimate they spent 1-3 years and lost $5,000-$20,000 learning through trial and error. Some never reach profitability and eventually give up.

Paper trading (simulated trading) helps you understand mechanics, but it doesn't replicate the emotional experience of watching real money disappear or the temptation to take profits too early. There's no substitute for real experience, but you can minimize the tuition cost by starting small and treating early trades as educational expenses.

Books like "Option Volatility and Pricing" by Sheldon Natenberg provide deep theoretical understanding. Educational platforms offer courses ranging from free YouTube content to expensive multi-thousand dollar programs. The expensive programs aren't necessarily better; much of the valuable information is available free or cheap if you're willing to invest time in research.

Finding a community of traders at similar experience levels can be valuable, not for "hot tips," but for discussing what worked, what didn't, and why. Online forums and local trading groups serve this purpose, though you should be skeptical of anyone claiming consistent, easy profits.

When Options Make Sense

Despite the challenges, there are legitimate reasons to trade options:

If you own a stock portfolio and want downside protection during uncertain times, buying puts can make sense. The cost is high, but sometimes peace of mind is worth paying for.

If you own stocks long-term and are comfortable capping upside in exchange for income, selling covered calls works. Just understand you'll occasionally miss big rallies.

If you have a strong, time-specific thesis about a stock (perhaps based on deep industry knowledge or unique insight), buying options provides leveraged exposure. Just ensure your conviction is based on genuine information advantages, not hunches.

If you want to gain experience with derivatives and financial engineering as part of broader market education, allocating a small amount of capital to options trading can be worthwhile. Consider the losses as tuition.

What Options Aren't Good For

Options are poor vehicles for casual speculation based on headlines or stock tips. The transaction costs, bid-ask spreads, and time decay make it nearly impossible to profit consistently from general market noise.

They're also unsuitable for long-term wealth building for most investors. A diversified portfolio of stocks or index funds, held for decades, has historically been the most reliable path to wealth. Options are short-term instruments that require active management and sophisticated understanding.

Using options to "make quick money" or "get rich fast" is a mindset that almost guarantees losses. The traders who succeed treat options as tools requiring study, discipline, and careful risk management, not lottery tickets.

Final Thoughts

Options are complex financial instruments with legitimate uses in portfolio management and risk hedging. They can also be powerful speculative tools when used with proper knowledge and discipline.

The overwhelming majority of retail traders who approach options as a way to make quick profits lose money. This isn't because options are a scam; it's because they're sophisticated instruments being used by unsophisticated participants who don't fully understand what they're buying.

If you decide to trade options, start by asking yourself honest questions: Do I understand implied volatility? Can I calculate potential profit and loss at various stock prices? Do I know the Greeks (delta, gamma, theta, vega)? Am I prepared to lose my entire investment on any given trade? Do I have a written trading plan with specific entry and exit rules?

If you answered no to several of these, you're not ready to risk real money. That's not a judgment; it's a recognition that options require substantial education before deployment.

For those willing to invest the time and accept the risk, options can add new dimensions to your investing toolkit. Just ensure you're learning for the right reasons and approaching the market with realistic expectations rather than dreams of easy profits.

Disclaimer:- Trading in securities markets carries substantial risk and is not suitable for everyone. Past performance is not indicative of future results. This article is for educational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Always conduct your own research and consider consulting with qualified financial professionals before making trading decisions.